I keep remembering that I and Western audiences have not seen our share of African cinema. Goethe Institut’s Africa Now series tries to mend that cinematic gap with movies like Soul Boy. This, by the way, is the first movie to come out of a partnership between Germany and Kenya to foster talent in the latter country. And as we’ve seen before, these collaborations produced good dramas with that dash of fantasy.

Soul Boy is New Kenyan cinema at its infancy, but all it needs is a simple concept to work. In Nairobi, 14-year-old Abila (Samson Odhiambo) runs to his mother’s (Lucy Gachanja) workplace. He tries to explain to her how his dad (Joab Ogolla) won’t open their shop because someone took his dad’s soul away. That won’t help his debts. She explains to him that his dad lost his soul long ago, giving him one of two options.

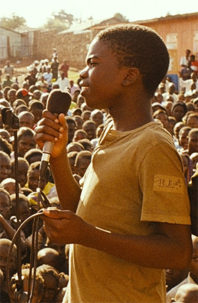

Abila, still a boy, can either run the shop on his own or get his dad’s soul back. He’s uniquely resilient, the movie showing how he wants to finish his goals. Meanwhile the other teenagers that we see here do lesser things like tease him and each other. Nothing will stop him from asking how to get to the Nyawawa (Krysteen Savane), the one who took his dad’s soul.

One of my favorite things about Soul Boy is its running time. At a whopping sixty minutes, it feels like a simple breeze as it shows Abila’s adventures. He, a Luo, even gets to recruit a Kikuyu gurl, Shiku (Leila Dayan Opou) to go to the border with him. Unlike his friends, she’s one of the few people who actually helps him with information about the Nyawara.

Abila and Shiku belong to two of Kenya’s biggest ethnic groups, clashing because of Kenya’s post-election violence. Showing them together means so much even to those who have no idea what happened three years before Soul Boy‘s events take place. But it of course means a lot more with the context, as they empathize with each other’s troubles. They have great chemistry and it’s disappointing that they’re not local stars after this.

It also doesn’t get as thrilling as that eventual meeting between Abila and the Nyawara. Happening in near complete darkness, Soul Boy introduces us to Africa’s nightmares and dreams although it references outside texts too. Reminiscent of The Thief of Badgad, the Nyawara gives Abila nine tasks so she can give his dad’s soul back. And these tasks seem insurmountable for the teenager, who must finish them by the next day.

The story has its cute tendencies Abila tries to finish his tasks, one of which involves riding a share taxi for free. Soul Boy doesn’t use the Nyawara’s voice overs but its presence makes the story feel slightly punctuated and clunky. There are also the signs that he has to follow, which get a little on the obvious side.

Other moments show the movie’s rough polish, especially in its visuals. Most of the film takes place under sweltering heat, the most archetypal visual that we associate with Africa. The share taxi takes Abila and his housekeeper aunt Susan (Katherin Damaris) to a white family. And one would expect that the movie would slightly change up its lok because of that different setting. But that’s not the case.

Abila ends up saving the family’s bratty daughter Amy (McLean Wilson) from a choking accident. Every character behaves accordingly after the incident, but there’s some unavoidable cringe worthy dynamics at play between then. It also doesn’t explore how often these encounters between poorer black characters and their richer white counterparts happen. Thankfully, those scenes are few and far between. Instead, there are more scenes where director Hawa Essuman explores Abila’s dreamlike states. And there’s always something universally appealing about watching a character grow onscreen.