“I won’t make shorthand films, because I don’t want to manipulate audiences into assuming quick, manufactured truths.”

-John Cassavetes.

Spoilers Henceforth for “Joker”

Come Sunday February 9th, 2020 at God only knows what time because the damn ceremony usually takes hours upon hours, there is a very real possibility that Todd Phillip’s Joker will officially be the first superhero comic book movie to win one of the major Oscar prizes. Going strictly by the numbers, the latest DC based superhero film is the most nominated film at this year’s awards ceremony. The Joaquin Phoenix led vehicle had an incendiary premier at Venice International Film Festival, with Lucrecia Martel awarding the film the prestigious Golden Lion despite the stated concerns of some hand-wringing critics. The film would go on to become the highest-grossing R-rated film of all time.

Biases upfront, I really didn’t like it.

Hi! Welcome to Big Hot Mess Season 2, the angry sophomore edition. We’re going bigger and weirder than ever before. Last year we started with my inexplicable favourite film of the previous year in Suspiria (2018). This year we’re talking about what is possibly my least favourite film of the previous year in Phillip’s Joker. Everything’s upside-down! 2020! A brand-new decade! Buckle-up kids!

I’m not alone in the camp of detractors. Joker’s many adoring fans were countered by a similarly ravenous host of detractors all too quick to lambast the film’s potentially toxic elements and general silliness. Normally, we try to provide as nuanced a take as possible when we try to recount what the various consensuses surrounding a messy film; the whys of why people may love or loathe our subject of discussion. Yet, it’s so difficult for me to fathom what someone would specifically get out of Joker that I would only end up not succeeding.

So, I’m not going to try and present an objective look at what others feel about Joker. Most readers are probably very aware of the varying discourses around the film already, and simply recapping them would merely be a waste of time. Instead, I’m going to provide an entirely personal account of where I feel that Phillips misses, and boy, is it a lengthy account!

Most readers are also probably aware of the ancillary background details surrounding the making of the film. Going all the way to the ground level, Joker is the latest enterprise from Warner Brother’s attempts to ape Marvel Studios with own line of comic book inspired films. Again, most readers are probably aware of this, and aware of the ensuing comic book movie wars that followed. You were either Team DC or Team Marvel, and the other side is making the films that were completely antithetical to the movie going experience. One’s making these dreadfully unfun slogs cloaked in darkness, while the other is building mass produced and cheap-looking exercises in fan-service. Never mind the fact that they’re both making what is essentially the same form of big loud nonsense with slightly different filters, there was an inherent difference to these films, and you need to pick a side.

When faced with the above ultimatum, most people picked Marvel. The last three years of DC related properties have been characterized by bizarre failure (future Big Hot Mess Candidate Justice League: #ReleasetheSnyderCut Edition) and forgettable things that are supposed to connect to each other (?) (Aquaman, Shazam). This is a treading water phase for DC. Maybe this might have some sort of use years down the line to our mega-franchise, but if it doesn’t, well, we have to have something.

It is in this landscape that Phillip’s original pitch feels somewhat revelatory. The supposed initial intention behind Joker was to build a stand-alone film, where one could build upon existing IP to make something fresh and exciting without feeling pressured to leave room for space to connect an overarching universe. For once, a superhero film is about its own specific story, and not the potential stories down the line. This will come back again further down the line when I get to what I think is the single most ridiculous moment within this film, so I implore you to please remember this paragraph.

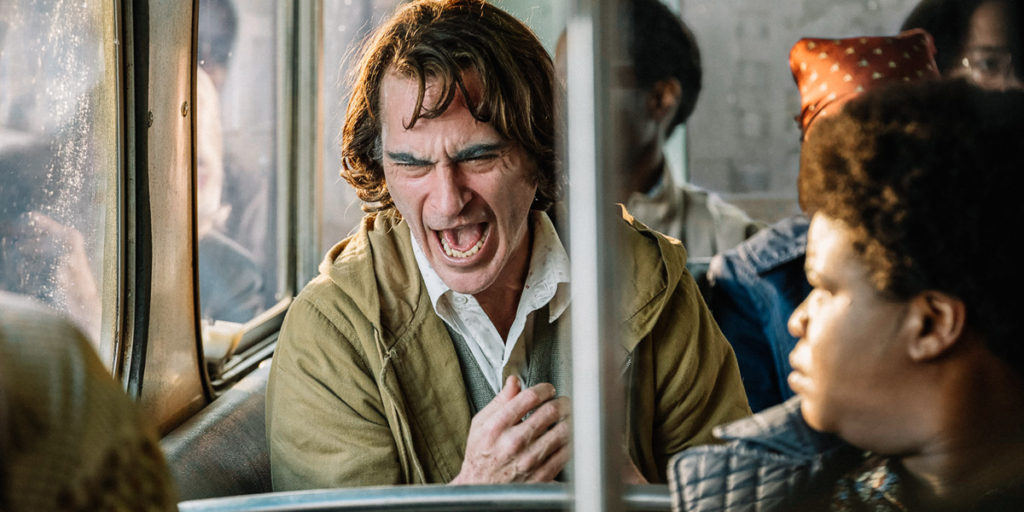

If I can summarize what I believe causes Joker to fall apart in one simple idea, it is that everything Phillips does is backwards. Theoretically, Phillips ask us to sympathize with a villain; in actuality he asks us to villainize a sympathetic character. There is a difference. By all measures, Arthur Fleck’s (Joaquin Phoenix) life is very sad. He’s an impoverished, mentally-ill loner who is struggling to get by as a party clown living in a decrepit, early 1980s Gotham City (the DC stand in for New York). He lives with his mother Penny, in a run-down apartment indicative of great class stratification. Arthur suffers from a mental disorder, which like all things in this film is loosely based on something else (in this case a condition known as the Pseudobulbar Affect) that causes him to laugh at inappropriate times.

These are some of the hardships Fleck must overcome. The only joy he seems to get out life is nightly viewings of a late-night talk show hosted by Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro). On paper, this man’s life is very sad! This could be the basis for a textbook poverty porn film.

The problem is that just about everyone who sees the film knows that the Joker is supposed to be the villain. As far as signifiers go, the Joker is one of the most instantly recognizable bad-guys in 20th Century Mass Pop Culture. This is what I mean by the film is accidentally asking you to villainize a sympathetic character. Whatever your base conceptions of what a Joker origin story would look like are, they more than likely result in your lead character becoming a violent anarchist, who really, really likes inflicting violence upon innocent civilians. Your first impressions of Fleck as a pure sad sack conflict with the nagging suspicion that “I’m really not supposed to like this guy for no other reason than the fact that he’s the titular Joker.”

Phillips relies upon the baggage we bring into this film throughout. Our entire basis for believing that Fleck is bad are based around the shorthand that we recognize from the pop-culture we’re inevitably aware of. This then conflicts with the fact that in order to counter-balance our mental perceptions of who and what the Joker is, we get the aforementioned double dose of misery. Nothing in Joker exists with a modicum of subtlety. Everything is designed with the quickest possible communicative signifier in mind.

Which is precisely what makes Joker’s fleet of references feel so hollow. Robert de Niro is in this film for some reason, presumably to invoke the spirit of Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy. “Joker is actually Taxi Driver,” is the next level of superhero reference galaxy brain to “Logan is a Western.” It’s the same sort of reference by association, where the feelings of something else are to be grafted onto this thing you’re presently watching free of charge. Superhero films are extraordinarily post-modern for this reason—they’re perpetually mimicking previous forms for an affect that is otherwise non-existent. Here, it is weaponized in the sense that forty years ago Taxi Driver made people uncomfortable, and thereby, this movie about the sad clown should as well.

Gary Glitter is in this film for some reason! Generally speaking, how I feel about Joker’s ineptitude can be summed up by the fact that Phillips uses what is possibly the laziest conceivable needle drop for what is designed to be a crucial scene in his film. “Rock and Roll Part 2” is a song which, Garry Glitter of it all aside, aged into parody about fifteen minutes after its conception. It is one of the most generic rock songs of all time, so much so that it would not surprise me if it were actually Garageband’s Stadium Rock loop. It’s here for what, temporal relevancy? Newsflash, the 70s were very musically diverse decade. Iggy Pop wouldn’t lend you the rights to “The Passenger” or something?

All of this shorthand makes Joker a tremendous bore. Fleck’s life is sad, but he personally is merely an uninteresting cypher for plot-related things to happen to. Phillip’s determination to absolve him of any sort of responsibility partially contributes to this. Bill Chambers articulates these frustrations better than I possibly could, and thus I quote:

“Joker does not, surprisingly, dance around the issue of whether or not Arthur is mentally ill (he is, and has regular sessions with a social worker (Sharon Washington) because of it), but cuts to city services eventually leave him without his meds. In other words, at a certain point in the story Arthur can no longer be held accountable for his actions. Such equivocation in the age of Trump is frankly moral cowardice, and I’d honestly have more respect for Joker if it were wholeheartedly the fascist daydream many are dreading. The guy who should’ve directed this is S. Craig Zahler.”

The last line here strikes me as particularly poignant, because in hindsight Phillips is possibly the worst director imaginable to lead a Joker film. Scratch that: he’s the best director for what a major studio would want out of a Joker film, but he’s the worst director to actually make an interesting film out of this IP. Phillips’ entire career has been predicated on having his cake and eating it too. Old School is film determined to lampoon the arrested development of its middle-aged “frat” boys, while simultaneously celebrating them. The Hangover films are meant to derive glee from the debauchery, but also, assert that they’re really good guys at heart. It’s a tactic that works great in comedy, because humour can be wonderfully drawn from juxtaposition.

It’s much less effective tactic in an issues drama. Phillips has routinely stated that his film is designed to be as apolitical as possible. He is very successful. This film is so determined to “both sides” its audience, that it essentially attempts to absolve itself of the inevitable interpretations of the film, as if the film is pointedly sneering at its detractors to say, “if you’ve got a problem with this, it’s your fault.” Joker gives you so little to go on aside from the very basic shorthand it is determined to convey, that your enjoyment essentially must come from whatever reading you’re grafting onto the film. When you realize that the film actually is devoid of anything meaningful to say, its treatment of women makes perfect sense. Of course they’re merely plot props, everything in this film is. Would you expect anything less from a film that is aiming performative false controversy? The film is so painfully normative, and Phillips is either unwilling, or unable, to suggest otherwise. This isn’t to disavow the film’s treatment of women, rather, it’s to point out another example of the film’s deep emptiness.

Joker isn’t fascist, but it’s boringly conservative. The real film that Phillips seems to be making isn’t Taxi Driver, The King of Comedy, or (hilariously) Akerman’s News from Home. It’s Charles Bronson’s Death Wish films, another excuse for on-screen violence dressed as an issues movie, that are what Phillip really seems to be invoking. It’s a film visually alluded to when Fleck runs down the vestibule towards a park in the dark after committing some real violent on-screen violence. That’s really what Joker ends up becoming, an insufferable excuse to say nothing.

I would be remise if I didn’t discuss Phoenix in some capacity. To give credit where credit is due, his performance is pretty much solely the reason we’re talking about this film at all. He and a very evocative score from Hildur Guðnadóttir just about single-handedly drag this tepid nonsense across the line. But like everything in this film, it too is overshadowed by the cloud of inevitability that follows this film around like a lost puppy. Chris Evangelista has the apt take that the performance is excellent up until Phoenix becomes Joker, where it all falls into self-parody.

The film falls into self-parody because of the film’s weakest element—it’s limp script. When Phoenix becomes Joker, he also becomes ostensibly a mouthpiece for the film’s thematics. The film may be apolitical, but it sure ain’t athematic. Every second of Fleck’s third-act Murray show appearance is insufferable, every line so obviously screaming “this is the point of the film,” that it caused Will Oldham in A Ghost Story to theoretically say “cool it buddy.” I have a very high tolerance level for cringe and cheese (see exhibit Black Christmas), but making a character in your film say “we won’t werewolf and go wild,” is patently ridiculous.

And yet, this isn’t even the film’s most ridiculous moment. No, Joker is determined to one-up itself by, once again, depicting the death of Thomas and Martha Wayne. Remember when I mentioned that this was supposed to be a singular stand-alone film? It’s baffling to me that a film that, for all intents and purposes, was supposed to be a singular entity spends as much time as it does invoking other comics-based culture. If this is actually supposed to be a stand-alone film, then why does it have to be a Batman origin story?

100% it does not have to be this way, but it is indicative of Joker’s priorities. Almost all of the information presented to you is cheap shorthand, offered as lazily as possible so that you can turn your attention to what the film really wants you to do—get a dopamine rush out of recognizing that “hey, that’s Batman’s origin story.” Maybe then, you’ll convince a friend to buy a ticket. Phoenix and Phillips marketed the hell out of this thing during its whirlwind press tour, where every day they found a new way to suggest that this was something incendiary that the powers that be didn’t want you to see. In reality, it was an inordinately successful guerilla marketing campaign for something that was tremendously staid.

Which is precisely why Joker has a great chance at some form of Academy glory come the 9th of February. When you peel away all the pomp and circumstance, what remains is an empty provocation that necessitates its audience to graft meaning onto it. It’s a film that wants you to focus on the big, loud performance at its heart, but can’t even properly achieve that. Really, it was always about the commodification of that pomp and circumstance, with the hope that you’ll pay more attention to the references to para-textual source material than to the film’s noticeable seams. The proof of this is that Joker 1 was made because it was a story about our time; Joker 2 is being made because Joker 1 made a billion dollars.