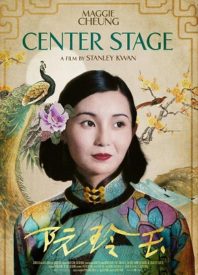

There’s probably a small subsection of film lovers who watch Stanley Kwan’s Center Stage. And that subsection wonders who else could have played the film’s protagonist Ruan Lingyu. There are at least three other actresses who could have filled those shoes at the time. Those actresses either got married and temporarily retired (Michelle Yeoh) or were working on other films (Carina Lau and Gong Li). The role went to Maggie Cheung, who was simultaneously working on other films. But this is the one that made the world take her seriously as an actress. The role is, after all, a challenge since the film requires her to play herself and Ruan.

There’s something interesting about Center Stage‘s contemporaneous scenes. The cheerful young actress and her co-stars (including Tony Leung Ka Fai) discuss the rumours that caused her predecessor’s downfall. These scenes show off its great cinematography, restored in a digital format. The early trailers for the film make it seem warmer and pastel-y, like the bright colours of Ruan’s outfits. But the contemporaneous scenes in this have the grain viewers expect from something out of the 90s. And during the period scenes, the cinematography seems slightly bleached. Ruan’s pale figure contrasts the deep wooden colours of the studio’s stairways. This version is also half an hour longer than previous versions.

This time around, Center Stage makes sure its viewers commit to every detail of her story. The script, on a text level, blames the actress’ suicide on man trouble. It eventually introduces the man causing that trouble, Tsai Chu-sheng (Han Chin). But the subtext here, as subtexts do, allow for more complex suggestions. The film plants it seeds through the documentary scenes. The first half of the period scenes, then, depicts Ruan both as an acting junkie and the primary caregiver for her family. Hardship existed for her, but mental illness isn’t apparent in this version of her in 1929, making her actions later on, or the anticipation of such actions, have more emotional weight.

The period scenes in Center Stage also hint at another reason for her emotional volatility. A war is the reason why she has to move around China. She, with her colleagues, avoid the air raids separating her from her family. And one colleague, Lilly Li (Lau), brings up the Japanese censorship of their film Little Toys. Li treats that creative stifling, one of a few, as a joke, but Ruan takes it more seriously. And when it isn’t showing how the national concerns the personal, its interests lie on Ruan’s feminist curiosity. This curiosity, shows on screen. Within six years she transitions from supporting roles to noble protagonists to mothers and sex workers.

Center Stage compares its reenactments to archive photos and footage of the real Ruan. In doing so, it argues successfully how much she was a woman of the 1930s China, doing anything to survive. She was a woman of the 1930s reflecting on questions that women of 1990s have their own versions of. Her story, as a protofeminist figure, is still relevant almost a century later. Women and people today are dealing with their own volatile situations that leads to their feminist reawakenings. That awakening can be stifled during the 1990s and even today, but that oppression was a bigger threat during Ruan’s lifetime.

The press destroyed both her and Tsai when their affair went public. Center Stage shows how that public excoriation affects their private life. She reminds Tsai of how much damage this news will cost both of them. Well, her more than him, and his only reaction is to physically abuse her. Kwan’s camera, as it should, concetrates on the close-up, on Ruan’s private moments. And during those scenes, both Cheung and Kwan collaborate to show a version of Ruan who is mostly a cold pessimist. She only shows her emotions when she’s withdrawing, a strange strategy that works wonders. This film, as a whole, shows how much the spotlight can destroy from within.