Hussein (Hossain Emadeddin) steal from a jewelry store. And a flashback scene shows him thinking about moving up from being a purse snatcher. These scenes prove viewers’ assumptions that this guy is bad news. But Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi use every minute of Crimson Gold to peel back layers into Hussein’s life. Sure, we find out the heart of gold within a part time thief, but the execution of that idea is amazing here. Outside of the occasional thief job, Hussein is a pizza delivery guy, and the camera follows him through every delivery. The camera captures what it’s like for a guy like him – bigger, neuro atypical, working class, etc. He does a job that has challenges that non-service people can’t foresee.

Making what seems to be his most straightforward film, Panahi cast a neuro atypical person for the character, even if he and the first time actor didn’t get along. Your move, Hollywood. Either way, the visuals and the sound design capture Hussein, based on a real person, driving through Tehran’s chaotic streets, grasping for air whether he’s climbing stairs or riding his motorcycle. One of those deliveries get Hussein to run into a guy who talks to him as if he taught him in college. But he’s actually his army supervisor. He’s gained weight after that army stint, which is something that also happens in the West. The guy tells him something about him being a real saint, showing that even the nicest people can take a turn.

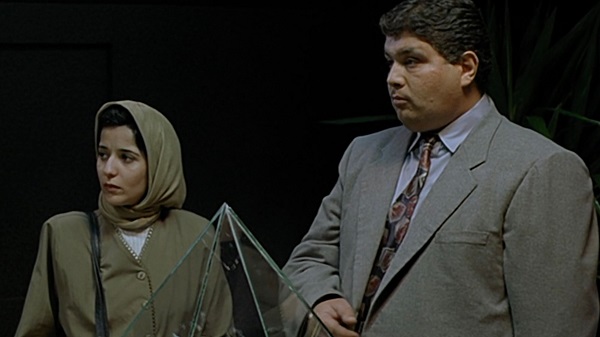

And the camera eventually captures where that turn can be. The next day, Hussein’s at the store that he eventually robs, thinking he can pass off as a rich man. He’s there to scout the place, doing so without the knowledge of his fiancée (Azita Rayeji) who was confused the entire time. Scenes like this ask the question of why a Godly country still divides rich from poor. This class divide, and Kiarostami and Panahi’s version of it, manifests in a scene or rather a whole act. Here, Hossein delivers to a rich man (Pourang Nakhael). This man refuses the pizzas because he ordered them from ‘sluts’ who ditched him. The man eventually invites Hussein in, which counters personal experience.

Normally, movies lose their viewers when characters act counter to personal experience. But there’s something fascinating about these characters’ decision making that make us pay attention. The more the man lets Hussein wonder from one room of his daddy’s penthouse to another, the more ridiculous the place looks. Panahi breaks a lot of cinematic rules here, trimming down his use of establishing shots to give the film a sense of anarchy. This is Panahi’s least human movie but in a good way and also his dreamiest. That last quality plays into all acts, especially the last one. And the more we stay with Hussein, the more we deny his involvement in the theft. But Panahi knows humans are more complex than that.