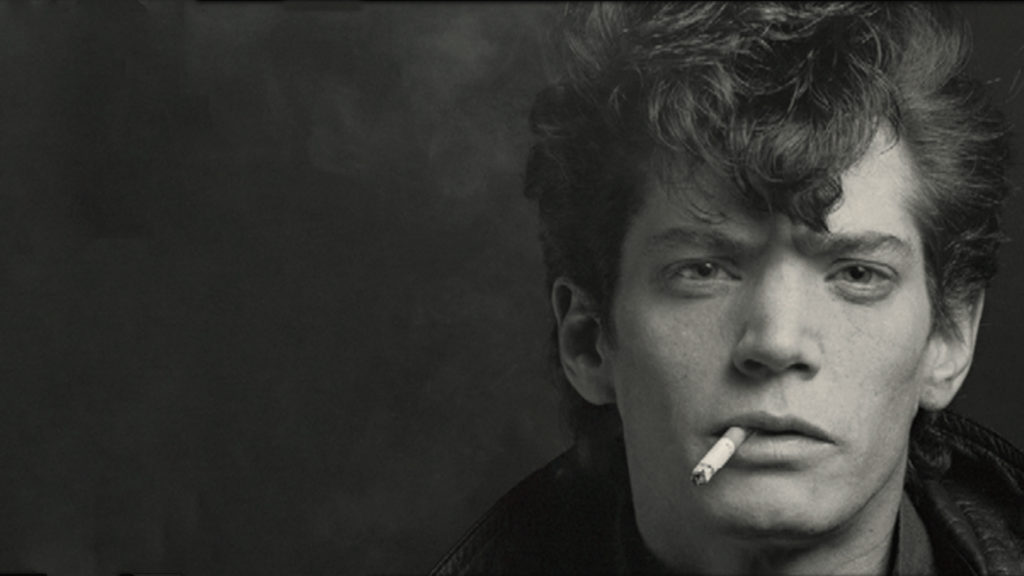

“Robert Mapplethorpe, a known homosexual, who died of AIDS. And who spent the last years of his life promoting homosexuality.” What a good way to go, I say. The words I quoted come from the late US Senator Jesse Helms, using homosexuality to shame the dead. What he didn’t count on, however, is my subversive sense of humour. Or that open homosexuals like me might reclaim our sexual orientation or AIDS. Perhaps, that we would subvert those aspects of ourselves from the negative connotations that conservatives have given them. That’s what Robert Mapplethorpe did in his final years.

Mapplethorpe is the subject of Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, a documentary that Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato directed. The subject’s reputation precedes him. That’s because he’s responsible for one morally objectionable picture. He has taken a lot of iconic photographs. But that one picture weighs as much of an impression as the others. Those pictures stun the straight laced suburbanites that Jesse Helms represents. As if those subjects were his only focus. As a man whose sexuality shocks people it takes a lot to get the same reaction from me. But that one picture does the job.

Bailey and Barbato, the team responsible for Rupaul’s Drag Race, have taken themselves to direct this documentary. They might not cover Mapplethorpe’s most controversial image but they touch on the ones that come close. They also peer into the reluctant photographer’s pragmatism in all sense and dimensions of that word. Ambitious people like him populates the gay world as well as the world of the arts. His personality type repulses some but attracts more people, and Bailey and Barbato lets us hear both sides. They actually do more than that, as they include archive tapes of Mapplethorpe justifying himself.

Mapplethorpe cannot speak against Helms nor can he with the people ambivalent about him like I am. That’s what the Bailey and Barbato’s documentary is for, a mostly comprehensive work taking us from the beginning. We see and hear from two of his siblings and the priest in his former parish. We also see and hear his classmates in Pratt, an art college in Brooklyn. Mapplethorpe’s own voice pops in as well. And we hear the archived voice of his equally ambivalent father. Together they serve are an important window in letting the audience see Mapplethorpe before he got his voice.

Bailey and Barbato’s documentary give us a portrait of their subject, Mapplethorpe, through more people who were in his life. That said, it’s difficult to watch this documentary and stay unbiased. That’s because some of those talking heads were alumni of a golden generation of Brooklyn hipstery. And pardon the sepiatone-tinted glasses but Mapplethorpe and his cohort actually did things. Things that didn’t seem derivative. Work that was organic and original. And he dated Patti Smith and the other talking heads talk about her as if they’ve seen her. Flesh and blood.

These perspectives are necessary to contextualize Mapplethorpe’s work. Among other things, Bailey and Barbato’s documentary follows us behind the scenes of a momentous retrospective of his work. The Mapplethorpe Foundation gave both the Getty Museum and the LACMA a total of 120,000 of his images. We see how both museums not just preserve the work. But they determine which ones of have the best aesthetic qualities. It’s a delight to hear curators from both institutions discuss his work in an academic manner. But the best moments from both curators are when they blush and use proper language towards queer subject matter.

One thing I’ll say about the film is that goes through the motions in the visual sense. They use a camera as a motif to transition from one talking head to another. Even the musical cues that heighten important moments of Mapplethorpe’s life remind me of those in Rupaul’s Drag Race. Seeing this, I searched for what makes this telling of the artist’s life more distinct that others. And in a sense, there’s something evocative about each b-roll clip, the flowers or the sculptural work in Brooklyn. These objects around him influenced his work and the way he saw things.

Mapplethorpe was methodical in work and his self-promotion as much as he was a user. His own voice over says it himself. He let other people around him use their money and resources for his materials. He cheated on Patti Smith with a man, the latter mentioning how inconvenient a conscience was. In a way, another thing that separates this subject and documentary from others is how it works as his contrition. Listing the shared sins of his cohorts, and detractors. Romanticizing people from the past is inevitable but this film chips away, showing us the human.

Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures begins a limited run at the AGO’s Jackman Hall today.

- Release Date: 1/18/2017