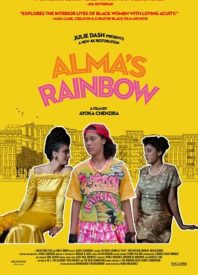

There has been a decision, conscious or otherwise, that cinephiles have been making in the past few years which involves the desire to see more films depicting the Black experience. Specifically, there has been an explosion of rediscovered Black films from the 1980s to the 1990s. Streaming services have been making a point to fill that need and so do cinemas. One of these recent rediscoveries is Ayoka Chenzira’s Alma’s Rainbow. It’s a film depicting the ADOS community and Caribbean people intersecting in Brooklyn during the 1990s.

Alma’s Rainbow got a restoration courtesy of the Academy Film Archive, and restorations like this make tours all over North America. In Toronto, the film gets screenings at the Revue starting on the 7th. Those screenings gloriously depict the testy but mendable relationship between its two titular characters. The first is Alma (Kim Weston-Mora), a woman who runs a salon. The second is her curious and growing teen daughter Rainbow (Victoria Gabrielle Platt). Playing one of her crushes, by the way, is Grey’s Anatomy‘s Isaiah Washington.

Alma’s Rainbow is unique to its time period. In fairness, I’ve only seen two other Black films from 1994. One of them is a typical working class documentary and another being unabashedly queer. This film makes it viewers feel at least two hundred years of history in ninety minutes, as its protagonists navigate a subtext of Black upper middle class milieu. That subtext also exists within its own precariousness. Specifically, Alma does her best to warn Rainbow about not going broke.

A major plot point in Alma’s Rainbow involves Rainbow getting her first period, and that plot point exposes both the film’s strength and weakness. That strength and weakness specifically comes from its casting. The costuming and Platt do a lot of work to convince viewers that she’s a girl reaching puberty, and yes, sometimes girls in real life are as tall as the adults around them. Sometimes blocking helps convince viewers that Platt is really a teen and sometimes it doesn’t. Some of the editing decisions also feel more stylistic than functional.

Nonetheless, some of these stylistic decisions don’t hinder from the film’s emotional impact. And to her credit, Platt does bring a lot of humour in telling Rainbow’s story. Growing up as a Black girl who has limits on choosing the woman she can become is a story that needs levity, which she brings. That choice, by the way, is between strict Alma and her aunt Ruby (Mizan Kirby), a flighty performer. Growing up sometimes mean that the path one takes begins to narrow, but that journey can still be a happy one.