Just last week, the head doctor who treated maligned opposition leader Aleksei A. Navalny for poisoning suddenly died. Not much of an explanation was provided for the death aside from old age. While officials close to Navalny suggest that old age almost is certainly the cause, mentally it’s impossible to not let one’s mind wander to the most lurid scenarios. One filled with conspiracies and shadowy figures draped in trench coats. Navalny himself is awaiting appeal for a two-year sentence stemming from an incident where he supposedly failed to check-in with parole officers while he was recuperating from said poisoning attack. You know, the one that supposedly came from Putin assassins.

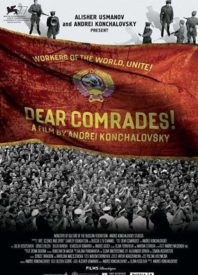

As Russia descends into mass protests and European diplomats find themselves expelled from the country, I mention all of this because it feels very much like Konchalovsky’s period piece desperately wants to be “the movie that the Russian people need right now”. This unfortunately leads Dead Comrades, the latest from the much-lauded veteran of the Russian and World Cinema scene, to feel frustratingly akin to an Oscar bait picture. Tellingly, the film has been designated as the Russian entry for Best Foreign Language Film. And yet, is probably meant to be a soft allegory on institutional abuses.

It’s a soft allegory due to its subject matter. Dear Comrades tells the story of a woman named Lyuda (Konchalovsky’s partner Julia Vysotskaya) at the centre of the 1962 Novocherkassk Massacre, a brutally quashed uprising that led to many deaths. The historicality of the film’s plot makes it feel like it’s definitely pointing at something to do with the modern day, but simultaneously remains at enough of a remove that the film is able to sneak itself by the censors. In a way, it feels akin to the soft criticism that Konchalovsky’s peer Andrey Zvyagintsev used to be able to sneak past potential censors.

The chief difference here is that Zvyagintsev is a filmmaker who is deeply conscious about all of the details of his image; he will quite literally use dilapidated and abandon architectural relics from the Soviet era as sets, and then shoot them entirely in slow cinema styled long takes, which accentuates the aura found within using such a location. In contrast, the period piece element of Konchalovsky’s filmmaking makes the mis-en-scene of Dear Comrades feel more about replicating 1962 in painstaking detail, or about manipulating the black and white in a way that stands out to the audience.

Let me be frank, the film is not helped in any way by its choice of format. While Zvyagintsev might be the most logical reference point in terms of Konchalovsky’s greater career, the real comparison point here is Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma, as both are films which seem to be using B&W as a form of artistic masking. At one point, a street painter is shot while wearing starch white linens. And a dark spot pools atop their right breast. It’s an arresting image, but an illogical one. There’s just no way a street artist has clothing that unblemished. Even worse, Konchalovsky does nothing with the 4:3 aspect ratio that the film is shot in. It’s there simply to provide an aesthetic of “old.”

While none of these choices are deal breakers for the film, they are indicative of where the film’s priorities seem to be. Once Lyuda’s daughter goes missing partway through the film, Dear Comrades begins to play itself and the beats of this feel very telegraphed. That Lydua starts as a staunch party member does little to help this, the metaphor sterilely fitting into her character shifts. Most of the ideas that Konchalovsky are delivered by dialogue, a missed opportunity in light of how often films of this nature need to be visually communicative too.

Yet, the film is frustratingly successful at being the middlebrow art piece that it so desperately wants to be. At the very least, Konchalovsky seems to understand the way that the B&W needs mutating patterns of light and dark. Specifically, Konchalovsky uses shadows and harsh lights to create beautiful images. Moments in Lyuda’s apartment are lurid, reminiscent of paranoid Eastern Bloc thrillers from names such as Jan Nėmek, Jiri Menzel and Karel Kachyna.

Not only that, but the way the film uses the natural sunlight is also arresting. It feels like it’s beating down upon the world, a spotlight on the past in some respects. The film is too beautifully designed, at least aesthetically speaking, to wholly dismiss. But it’s also a film that is far too clean for what it needs to be. Dear Comrades is very sterile, made with surgical precision. I just wish it was a little more willing to paint outside the lines; in that case, we might have gotten the film we really need right now.