Happy Easter everyone. I hope that you’re all safe and healthy where ever you are.

Being upfront here, large portions of this piece originally appeared on my Letterboxd account, which is usually where I brain dump most of my immediate thoughts on films. I have since lost the plot on this attempt at a live journal. I don’t want to dwell on how what my mental state has been, because it has been very not good, but also, I doubt it’s all that dissimilar to the vast majority of you.

Part of the problem with trying to do this at a consistent daily output is that it’s real difficult to conjure up thoughts on things you have no thoughts on. It’s not fair to those of you take the time to read what I write if the output is scrambled forced ramblings about Jupiter Ascending. Many of you are probably struggling with deficiencies in concentration at present. Regaling you with tales of about how I can’t focus on the Wachowski’s doing The Fifth Element does not sound like a valid use of any of our temporally realities.

The Insider is different. It’s not the first film in two weeks that I’ve had real ideas about, but it’s the first film in a few weeks that I’ve really felt in addition to these ideas. What we want from the cinema is an inherently personal exercise. From my own narcissistic perspectives, mine is obviously the most correct version of such an exercise, and that, dear reader, is that I want to see films that hit me and I can’t really explain why. What I can do is write and discuss ad nauseum, the jumble of idea strands I’ve considered. Nothing is good, and nothing is bad, but rather, everything is a version of an experience we wish to have.

The Insider is very much an experience I wish to have. It’s an investigative thriller, a conspiracy film, a spiritual retelling of All the President’s Men. It’s that film, mashed to a deeply cynical exploration of the totality of the world in which we live.

My knowledge of Mann is pathetic, so maybe someone can help me out here: is The Insider considered one of his better films, or am I merely elevating it because it feel akin to being a prototype version of Haynes’ Dark Waters? Haynes’ most recent soon-to-be cult piece of Oscar cinema works in a similar fashion to this, albeit in a simultaneously more and less cynical manner. They both ultimately about the totality of the structure, wherein the litigious battleground becomes that of the very soul of America.

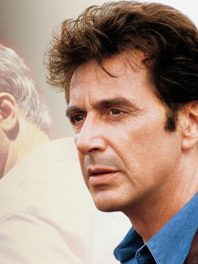

Al Pacino’s Bergman (a damn good Pacino performance) informs Mike Wallace (Christopher Plummer) that was has been broken cannot be undone. There are two scenes where we can see what has been broken, but is only being revealed to be so. As whistleblower Jeffery Wigand (Russell Crowe) is informed of the potentially dire ramifications of speaking out, we see him rapidly processing what he’s going to do without varying forms of insurance. It harkens back to an earlier moment where Wigand informs Bergman that he took the original job simply because it paid well and came with good benefits.

The duality of these two scenes suggests the ways in which the American structure weaponized the rhetoric around meaningful labour, and tethered its necessary social safety nets to employment, something that could be “accidentally” dropped in a moment of crisis and morally vilified for justification thereafter. Wigand’s journey of employment goes from being a literal health inspector of a tobacco company (a beyond meaningless job) to a high school chemistry teacher (a job I’d like to believe is meaningful (and that scene where he begs for a teaching job hits real close to home in the present moment)). It’s in that transition where the corporate shackles are slapped on. Our world is run by corporate legality.

David Graeber has an essay titled (and pardon my French here) “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs.” It undoubtedly has its faults. It’s core Tennent however, recognizes how the network of entangled bureaucracy that, theoretically isn’t supposed to exist in capitalism, is the fundamental cornerstone of most jobs. The chief intervention of his piece is to point out the absurdity of positions like private equity CEOs and PR researchers. And hey, I don’t wish to denigrate anyone’s position as being non-essential. I too have worked my fair share of jobs that are probably non-essential when you really want to break it down. What Graeber seems to be getting at (and he allows for some exceptions) is revealing the phenomenon of capitalism whereby the further you are from the direct impact upon others, the more you are paid. What particularly draws the brunt of his ire are the positions that reinforce this inequality, and also the inequity itself.

Since this is a film site, let’s talk in terms of film production. The grips, boom operators, and direct set hands are probably the lowest paid members of any film production. This is despite the fact that they literally hold the apparatus. Then you end up with supervisors, actors, and directors. This structure rolls all the way to the top, whereby those receiving the bulk of the wealth are the executives. The justification for such an imbalance is that the very top ultimately makes the decision on what gets made, and they do so through the guidance of marketing and research. You can see this in the narrative surrounding the film Cats, whereby the VFX hands took the fall for the film’s underperformance and subsequent enshrinement into meme lore. In reality, director Tom Hooper’s insistence upon a peculiar visual design that emphasized a version of (insane) realism probably caused more harm than the overworked VFX crew did. And on top of that, the real culprit might be the executive branch which determined that “Hooper+musical=Oscar and thereby $$$.” But the VFX crew got mocked at the Oscars; the higher-ups remained unscathed.

Precisely what makes The Insider so fascinating is its meta shift form Wigand’s ordeal to Bergamn’s. When the film becomes a piece about who really control the message, is when this really being to, as the kids say, “be hittin’ different.” We watch in real time as what is broken is revealed to be so. Bergman makes the news, but corporate prevents him from doing so. Does that mean the corporate lawyers, a profession that grew into being in the 20th Century, really control the news? And by extension, does that mean that corporations actually control the message? If you don’t believe me, let me point you to exhibit “steak-ums has gone sentient.”

Right now, there is a lot of rhetoric about how “we’re learning what is really essential to the running of our society.” Undoubtedly, it is a wonderful sentiment, that is actually a bit of a misnomer. You see this in everyday parents revealing how much they’re struggling as educators, or in the nightly make some noise for you frontline health care works. Definitely do not stop with this. But it is only half the equation, and the other half needs to be the recognition of how these systematic inequalities vilified such positions in the first place. What we’re actually learning about is the tremendous grace and consistency demanded of ordinary people under perpetually extreme circumstances, thereby made more difficult by the ensnaring structural networks that surround them. These are those essential to the competent running of your society. Pakula directed us to follow the money, but what happens when the money learns to fight back?