Spoilers thus forth for A Wrinkle in Time.

I’ve realized that the reality of writing a column on films that are messy, is that the majority of these films are the result of a visionary filmmaker given far too much control for their own good. Don’t get me wrong, there are definitely messes created by there being too many cooks in the kitchen—Suicide Squad, Dune (1984), and Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 all stand out as examples—but the majority of the films that will be covered for this column are ones that could very well be described as the idiosyncratic vision of someone with far too much hubris for their own good. Unfortunately, the side effect of this reality is that the aforementioned hubris is all too frequently attached to a male voice. Thankfully, there are definitely some female voices in there; Elaine May’s Ishtar, Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Teknolust, Catherine Berillat’s Fat Girl, and Christine Cegavske’s Blood Tea and Red String, all could (and likely will) make great editions of Big Hot Mess at some point down the line. But the fact of the matter remains that for all of the talk about how diversity is important to an ever-changing Hollywood, of the top 250 grossing domestic films in the year 2018, just 8% were directed by women. In a world where it takes Lynne Ramsey six full years to make a small pulpy thriller after three certifiable masterpieces, the likelihood of there being Claire Denis’ Southland Tales is disturbingly too close to non-existent. Claire Denis’ Southland Tales would be magnificent for crying out loud (High Life will be released April in select theatres everywhere) and keep your eyes peeled because we’ll probably have a contest of some sort here at In the Seats. (EDITOR’S NOTE: We certainly hope so!)

However as previously pointed out, female directed idiosyncratic visions made on a large scale do exist. One, is A Wrinkle in Time Ava DuVernay’s adaptation of the classic young adult novel of the same name; a film carrying the distinction of being the first directed by a woman of colour with a budget of over $100 million. Only took a hundred some odd years of feature filmmaking to get there. Released roughly one year prior, DuVernay’s film was her first following her much lauded 13th, a documentary emphasizing systemic racial injustices in the American legal system. As well, A Wrinkle in Time was DuVernay’s return to fiction filmmaking following the successful Martin Luther King biopic Selma, whose lack of Academy Award success in 2014 served as a foundational building block for the, “Oscars So White” movement, which inevitably led to changes for the better within the Academy Awards voting body structure (to a certain extent).

A Wrinkle in Time was marketed very aggressively alongside Black Panther from a month prior, with a reported advertising budget of somewhere in the two hundred million dollar range. I started by mentioning the reality of the connection between A Wrinkle in Time’s budget and DuVernay’s role as director, because seemingly it was impossible to mention the film without mentioning the importance of a woman of colour actually directing a film on this scale. For better or worse, diversity remained the key buzzword defining A Wrinkle in Time in the lead-up to its release, where one could argue that it looked like the Afro-futurist baby cousin to the more adult and similarly Afro-futurist Black Panther from a month prior.

This is probably a good place to try and recognize my privilege to the best of my abilities. There are realities of A Wrinkle in Time that I can only empathetically approximate, because they are very much realities that I do not have to confront on a regular basis. I am a Chinese-Russian-Canadian; who was born in Edmonton, Alberta; who is also mostly straight, and grew up in normal middle-class household with two parents. I have never been, and never will be, a young black girl with mixed race parents. As universal as the message attempts to be, the film is also filled with specificities that are wonderful, and are probably more wonderful than I can truly give them credit for.

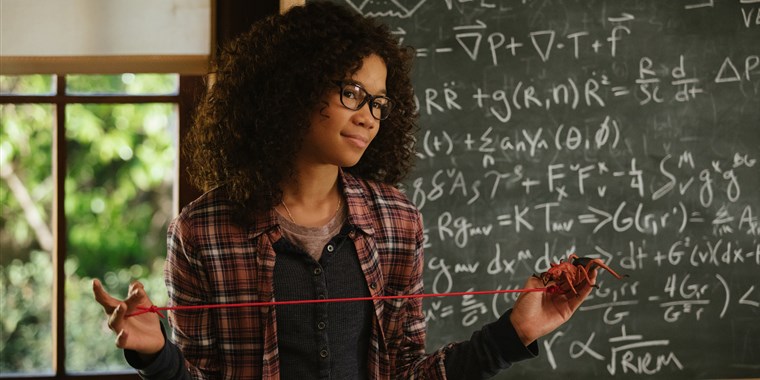

The actual truth to power of A Wrinkle in Time is something I can guess, but is also something I’d prefer to cede the flood to someone whose voice is much, much smarter than my own. Writing for Slashfilm, Monique Jones’ review for A Wrinkle in Time is a review I can confidently proclaim as the best serious review I read on any film in the calendar year 2018. It is a highly recommended read, and one that is deeply honest about the dilemmas associated with being a female critic of colour reviewing what is ostensibly the biggest film ever made by a female director of colour. Jones aptly touches upon the message of A Wrinkle in Time being inherently tied to the “concept of mattering,” while pointing out just how meaningful that actually is when it’s tied to the journey of a young biracial girl discovering “that the attributes” she hates the most, “can actually be the attributes that attract people the most.” Specifically, Jones touches upon the multiple scenes where Calvin (Levi Miller) compliments Meg’s (Storm Reid) hair and smarts, considerably special because “he’s complimenting the two things black and biracial girls are often told aren’t beautiful.” Regardless of your understanding of the film’s technical quality, the film’s thematic quality is beautiful. Simplified to a message of self-belief, A Wrinkle in Time is a message that Jones confidently asserts “can only do good for its young viewers.”

Yet somehow this positivism was, surprisingly, considered to be one of the many notable drawbacks of A Wrinkle in Time. Indiewire’s Dave Ehrlich in particular claimed that A Wrinkle in Time was “too emotionally prescriptive to have any real power.” He was not the only detracting voice. A Wrinkle in Time currently sits at a crisp 42% on Rotten Tomatoes, with other notable complaints including too heavy of an emphasis on mediocre CGI, and a plot bordering on the point of somewhere beyond nonsensical. Let’s tackle the second and third charges before the first. I loathe CGI in just about all forms, and boy does A Wrinkle in Time contain some of the more ridiculous examples in recent memory. To provide an example, at one point Reece Witherspoon turns into a giant flying piece of swiss chard. There’s a giant Oprah that’s very clearly just Oprah in front a green screen, thus failing to meet the cardinal goal of CGI where the magic is too recognizable to be any amount of illusory. At the same time my brain didn’t really care about how clearly fake the image was. There is a very personal enjoyment to a giant Oprah. My enjoyment; however, is entirely tied to the giant Oprah, and is not necessarily tied to the any sort of believability in the image. The broken verisimilitude unfortunately provides an unwanted distraction for many.

The imaginary world that DuVernay would like to create feels much less imaginary, and far more constrained by the technological limits imposed on the film. It is more difficult to understand complaints regarding the film’s plot, without feeling as if there is a bit of a central fallacy being missed to the way DuVernay has crafted her film. Kim Renfro from Insider points to the film’s “frustrating lack of explanation,” to suggest that things just seemingly happen inside of the film. As a pure propulsive narrative, A Wrinkle in Time is more than a bit meandering. The film takes roughly an hour to make it out of its roughly expository stages, with the midpoint coming over halfway through the physical midpoint of the film. But A Wrinkle in Time is arguably more tone poem than it is pure propulsive narrative. The scene that hit me the most is when Meg finally meets her Dad (Chris Pine). The half joyous half incredulous sob she emits is so shatteringly real that it becomes nearly impossible to not believe the raw emotion her character feels in that very second. The colour schematics meanwhile accentuate this feeling of pure love, with the warm pink and orange hues in the background providing an enveloping feeling. The tonal emphasis of colour schematics is a thread throughout this film, jumping back all the way to the misunderstanding principal’s (André Holland) office in the film’s initial stages that is monochromatically dressed, and clearly metaphorically tying into Meg’s dour emotional mood.

Ultimately what is special about A Wrinkle in Time, is that while the message may be a touch prescriptive, the central protagonist never becomes a cypher for said message. Her journey remains her journey. All of the pockmarks of the film fall away when you realize that Meg’s journey is one of opening her heart to those around her, as communicated through a lyrical use of cinematic grammar and colour schematics, and not simply raw expository information. DuVernay is ultimately not concerned with progressing from step A to B to C in a logical and timely manner, but rather, is far more engaged with exploring what exactly “A” means to the characters that inhabit its world. Characters that are after all—the tender age of just thirteen.

I strongly considered if I should try and connect my present reaction to this film, with what I could imagine my thirteen-year-old self would think of this. I then realized that was something impossible to properly do. The experiences that took me from then to now have so fundamentally shaped the present individual that I am, and a result, are inseparable from the way that I interact with my world.

If the person I am today says, “I kind of dig parts of this,” then I kind of dig parts of this. To amalgamate Ehrlich and the fifty-eight some odd percent of Rotten Tomatoes critics who dug far less of A Wrinkle in Time than I did into one group (which is sinful and I will chastise myself later for it), that inability to be thirteen again probably attached itself to more than a few of those reviews.

There are two legacies of A Wrinkle in Time. One, is the legacy of being the first film directed by a woman of colour with a nine-figure budget. The other is as the film that the critics (read mostly white guys like Ehrlich) destroyed, or didn’t depending on what you believe. In a rousing speech advocating for more diversity in film criticism, Brie Larson alluded to how she “didn’t need a 40-year-old white dude to tell me what didn’t work for him about A Wrinkle in Time.” Immediately her comments reached a backlash, from voices fixated on her choice of an example. The mess of A Wrinkle in Time is less concentrated on the screen, and more concentrated on the discourse surrounding it. Your reaction now carries a valuation judgement, and there becomes a right and a wrong way to watch the film that is solely tied to your most simplistic normative judgment of it. In a way Larson’s comments remind me of a Jessica Ritchey think piece I read months ago on the fallacy of vocally stated “unpopular opinions” that denigrate the veneration, or lack of it, for a particular piece as being simplistically tied to “placing the blame on the safest, easiest punching bag.” This sort of normative binary is unfortunately becoming more and more commonplace. Playing cultural politics through an evaluation of the most basic response one could have to a piece of art, only serves to obfuscate what is both problematic and special about that piece.

In this case is the softest punching bag the critical industry itself? Maybe. But on the other hand, the backlash against Larson’s points gangs up on her example as the easiest punching bag. The much more difficult punching bag to get at is the all-encompassing nature of what could possibly cause A Wrinkle in Time to fail to make money. There’s a multitude of factors at play here, all largely ignored by a fixation on what the correct answer in liking or disliking A Wrinkle in Time is.

The messiness of A Wrinkle in Time extends beyond the screen to the film’s inherently commercial nature and heavy celebrity presence, but also to the fact that the film will always be the first film directed by a woman of colour with a nine-figure budget. The harder punching bag to get at it implicates us all, you and I both. I am implicated, because I failed to see this film in theatres a year ago, even though I probably should have (I enjoyed the hell out of this film). I am also implicated, because as much as I disagree with Larson’s complaints that A Wrinkle in Time was unsuccessful as a result of white critics, I have thus far largely glossed over the more important point she makes. There is an imbalance within the industry both within the actual production and criticism of cinematic works. There is an imbalance within the fact that it took over a hundred years of feature film making for a woman of colour to get half the budget of Transformers: The Last Night. Yet, there is also an imbalance within the industries that critically evaluate her film, in that the array of voices is far too homogenous to be reminiscent of the realities our larger world. Further still, there is an imbalance within the fact that we’re not at a point where A Wrinkle in Time’s can have the space to breathe that a film directed by a man will have.

These are imbalances that we may never be able to truly solve, but we are implicated to try and rectify said imbalances. We solve that imbalance by supporting strong voices, especially if they are diverse ones. Putting my money where my mouth is, I can specifically point to three—Victor Stiff, Paolo Kagaoan, and Courtney Small—that frequently contribute to this site. We fail when we get tunnel vision on the semantics of binaries. We rise when we see the whole picture.