Ah, the summer. The whipping boy of edgy cinephiles everywhere. The season in which the weather is hot, the kids are out of school and bored, and the cinema remains a safe haven of air conditioning. The time period for film in which each week brings about a new blockbuster, a new must-see film, a new box office titan.

Considering that there were five 2000+ screen new releases last week (one of which is an Angry Birds 2 film no one asked for), it’s fair to say that this the doldrums of the summer movie seasons. The point where major studios go, “I dunno, you guys wanna see a third ‘Gerard Butler fights terrorists’ film?’ We’re just as surprised that he’s still around as you are, believe us.” At this point, people usually like to take stock of how the summer went. What’s unique about this reflection is that when you consider the summer movie season, you are partially required to consider the financial results. Unlike building a retrospective at a time such as the end of the year where you can almost exclusively limit your focus to quality, thinking about the summer at the movies must consider the quality of those films that scored the largest quantity of tickets.

This summer in particular has been a weird one. We officially have a new highest grossing film of all time. Not only that, but this new highest grossing film of all time is one that a substantial number of people seem to really like (Avengers: Endgame officially has a Rotten Tomatoes score of 94% at this moment). The movies that money were also generally agreed to be good people! Fly a “mission accomplished” flag atop Cinderella’s Castle.

This summer has been a weird one not because of the fact that some of the highest grossing films correlate to relatively fine filmmaking, but rather, because if there was ever a summer for you to jump aboard the “cinematic apocalypse hot take train,” this is possibly the peak moment to do so. Every summer people fire off takes like this one from Mark Harris, about how the litany of sequels, caped crusaders, nonsensical chase-based animated films, and dog films with dog-based humour, are like, destroying cinema or something. Takes like this at the end of every summer are about as constant as the sun setting in the West.

For the first time in years, however, it feels like it is at least worth considering the possibility of a cinematic apocalypse when thinking about this summer. Considering, while maintaining the steadfast recognition that there’s no such thing as a cinematic apocalypse, but considering nonetheless. In a clarification to his original tweet, Harris points out that the real harbinger of change here is that the top ten is littered with sequels, and that these sequels have dominated the box office to the extent that they have. Furthermore, the addendum that needs to be added to this litany of sequels being so successful, is that they are largely all from the same studio. Five of the top six grossing films of the year thus far are all Disney films. The sixth is Spider-Man: Far from Home, which, as part of the MCU’s larger framework, is ostensibly Disney. All of these films have grossed obscene amounts of money, at this point collectively totalling in excess of two and half billion dollars domestically.

Fly a “mission accomplished” flag atop Cinderella’s Castle?

This is largely the cause for concern. As much as someone who writes a column titled “Big Hot Mess,” can possibly have, I have little issue with the fact that highest grossing films of the year are mostly variations of sequels and remakes, essentially various forms of repackaging for existing IPs. Hell the film we’re going to talk about today is a remake. The question worth shouldn’t necessarily be, “is this creative bankruptcy at its finest,” but rather should be, “should any one film (or type of films) be this successful.” The answer to the first question is self-fulfilling, and akin to screaming into the void. The second offers a lot of room for interpretation. What if that one film was beloved? Would the monopolization of the cultural conversation be okay then?

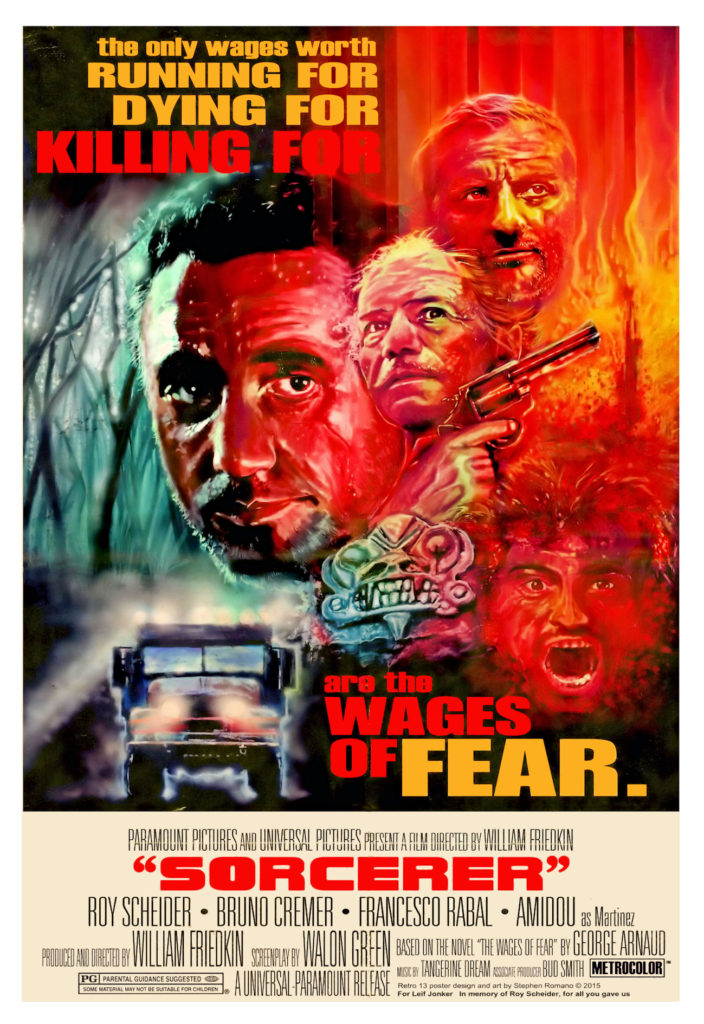

Enter exhibit Sorcerer aka William Friedkin’s follow up to The Exorcist aka one of the films that got roundly trounced by Star Wars at 1977 summer at the box office. Sorcerer is not one of the aforementioned hyper-successful films. It is actually one of the all-time great box-office failures. It is also an excellent film that has since grown a considerable cult following (of which I am obviously a card-carrying member). It is a lot of things to a lot of people, but most importantly, it is the last call for a time period that, rightly or wrongly, is frequently referred to as Hollywood’s most creative period. Thus, here at the end of the summer to end all summers at the movies, I figured we could have a discussion the things that get lost in the “inevitable” wake. In this discussion, maybe we can see that the mess might actually just be a symptom of suddenly changed tastes, that were hip one minute and cringe-worthy the next. To quote an old man yelling at a cloud: “I used to be with ‘it,’ but then they changed what ‘it’ was.

After last week’s confession regarding my distaste for Stranger Things, I feel like it’s prudent to further alienate my reader base by vocally pointing out the fact that my tastes have moved away from Star Wars, films that I once loved in my early youth, but have since come to regard less highly. It’s prudent, however, to discuss Star Wars though when talking about Sorcerer. The parallels between the two, or rather lack thereof, largely define why one was a massive success and the other got lost in its wake. Thus, I think it’s important to recognize what Star Wars is. Lucas’ film is a space opera, and a fairy tale. It’s a damn good fairy tale, but it’s a fairy tale nonetheless. It’s a basic good versus evil story. It has a predestined happy ending.

Friedkin’s film is none of those things. It’s a remake of The Wages of Fear staring Roy Scheider, who has just come off of Jaws and The Marathon Man. It was Friedkin’s follow-up to The Exorcist, which meant that he had far more creative control than he ever should’ve been given. It is a depressingly bleak film with a wild high concept, where four men are tasked with transporting four trucks of highly volatile dynamite across a South American jungle, and any sort of bump in the road could send them straight back to god. It’s about as far from Star Wars as you can get.

Sorcerer is not a good against evil story. Friedkin has a long first act, with almost zero English dialogue, where the sole purpose is to introduce us to each and every one of our “heroes.” Except, these “heroes,” are anything but. We witness them commit several crimes, three of which are murders. These are not good people. They do not have altruistic motives. Their response to eventually taking the highly dangerous job, is to demand double the pay and political asylum.

The purpose of this opening, however, is twofold. It is to frantically blur the line between hero and villain, and also, to point out that these are each men who have in some way cheated death. Their punishment is exile to the jungle. Their penance is to metaphorically descend into hell, only, there is no escape. What I love about Sorcerer is that Friedkin is determined to hammer home his theme as hard as possible. As he would later comment, “no matter how much you struggle, you get blown up…fate is waiting around the corner to kick you in the ass.” The set-up is that they have all cheated death. The question is can they do it again? The answer is a resounding no.

Yet, while Sorcerer’s theme is clearly pronounced, the reverberations of that theme raise questions that the film wants you to answer. Despite crimes by these men, the film forces you to reconcile with your feelings regarding their predetermined ending. This is where the film strikes a tenuous balance that’s normally very difficult to pull off. Early on in the film, maybe fifteen minutes in, one character comments that, “no one is just anything,” suggesting that we all contain multitudes of personal permutations and possibilities. Our pasts should be absolved, but they also should not define us.

But Sorcerer’s intentions are not purely focused towards a didactic conveyance of theme. Arguably, Lucas’ greatest strength is the film’s use effects and well-executed action set pieces, that provide immersive thrills to a galaxy far, far away. Yet, Friedkin’s film is equally as adept at its action sequences, if not more so. The magnum opus is obviously the film’s infamous bridge sequence, a scene that I defy anyone to watch and come away with a reaction other than awe. It’s a moment that necessitated a complex hydraulics-based pulley system, a location change, and literal buckets of imported water, to craft a visceral moment of rapt tension and hellish conditions. It looks like hell. It must’ve been hell to get.

Hellish is probably the best description for Friedkin’s shooting style. Most of my knowledge of the film’s production comes from a segment of Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, a fascinating portrayal of the New Hollywood Era that probably contains a liberal blurring of the line between fact and fiction. Friedkin struggled to properly stick to a shooting schedule. The budget ballooned. Executives were (probably rightfully) livid. Friedkin fired people left and right. All of this was covered by the press during a time when stories of a nightmarish production still had an effect.

If there is one thing I sincerely believe about Sorcerer, it is that if the film had been released two or three years earlier, it would probably have a place in a larger cannon of great films from a revered time period. The New Hollywood is a weird phenomenon in cinematic history, and must be discussed in relation to Friedkin’s film. On one hand, as the greatness of the New Hollywood is often grossly overstated. On the other hand, it’s impossible to look at the years 1968-76 and not realize that there were a lot of really good American films of a specific tone and tenor.

Yet, all of these films have a similar tone and tenor, a tone and tenor that Sorcerer largely matches. The bleak pessimism of Friedkin’s film fits right in with the anger of Arthur Penn’s Night Moves, or the depressed post-Watergate pessimism of The Parallax View and The Conversation, or even the heavy outsider realism of Barabra Loden’s Wanda. Star Wars is the aberrant vision to those things, more in line with the serialized stories it draws from. But to reiterate, these films are for the most part, of a similar ilk. I’ve been a college student for long enough to know that eating ramen every day in order to pinch pennies is a terrible way to continue to enjoy ramen. I’m at least self-aware enough to recognize that, as much as I love American 70s cinema, I too might have gone a little loopy by 1977 if force fed a steady diet of dour vision upon dour vision.

To bring the conversation back to today, we’re in the midst of a time where it seems as if we’re getting a lot of ramen. At the moment, it’s because there’s enough people that really want ramen to justify a steady diet of it. But eventually people will tire of ramen. Maybe it’ll be tomorrow. Maybe it’ll be a couple of years down the line. Maybe, it’ll be in 2027 when the photo-realistic remake of Home on the Range drives people up the wall. The day, however, is coming, and a new taste will take its place atop of the cultural food chain. Cinema goes in cycles, and sometimes, you’re the one that gets spit out and lost in the wake of the new muse.