If you’re a Canadian, then you’ve likely seen some of the Canadian content ads that have graced the pre-show screens of multiplexs across the land in the past few months. Most of them include a gruff, “in a world,” style trailer voice listing off things that Canadians have technically contributed to. Some of these include the fact that The Handmaid’s Tale was shot in parts of the Greater Toronto Area, and also that Mr. Deadpool is from Vancouver, examples which are hilarious to me because they’re not actually made by Canadian studios. And while I recognize that it’s kind of difficult to build a marketing campaign around Atom Egoyan’s Exotica, it’s not exactly a great look for your, “Canada: we sometimes make okay things,” commercial to have a number of prominently American sources with an ancillary Canadian connection.

Part of the reason commercials such as the aforementioned one need to exist at all, is due to a much-needed image rehabilitation regarding Canadian content. Because of its close proximity to the United States and its world dominant cinematic industry, Canadian cinema has struggled to gain footholds within its own country. A sort of inferiority complex occurs, which leads to allegations of cultural cringe. Most of this hand-wringing is unfounded. I’m certain one could rattle off a list of a dozen great Canadian films without even breaking a sweat, a list that could include great titles such as, The Brood, My Winnipeg, and Stories We Tell.

With that being said, where Canadian cinema struggles in comparison to its Southern counterparts, is in the art of audience finding. At times, these films struggle to find an audience, making funding difficult. To combat this, Canada has a subsidized film industry. Often, this process works out great. A film that otherwise wouldn’t get made, gets a chance to shine because there’s a budgetary cushion to finish the film. Sometimes, however, this process leads to a case of too many cooks in the kitchen, as evidenced by this week’s case study Face-Off.

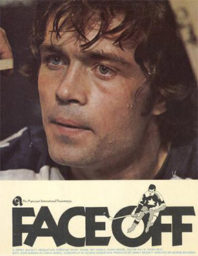

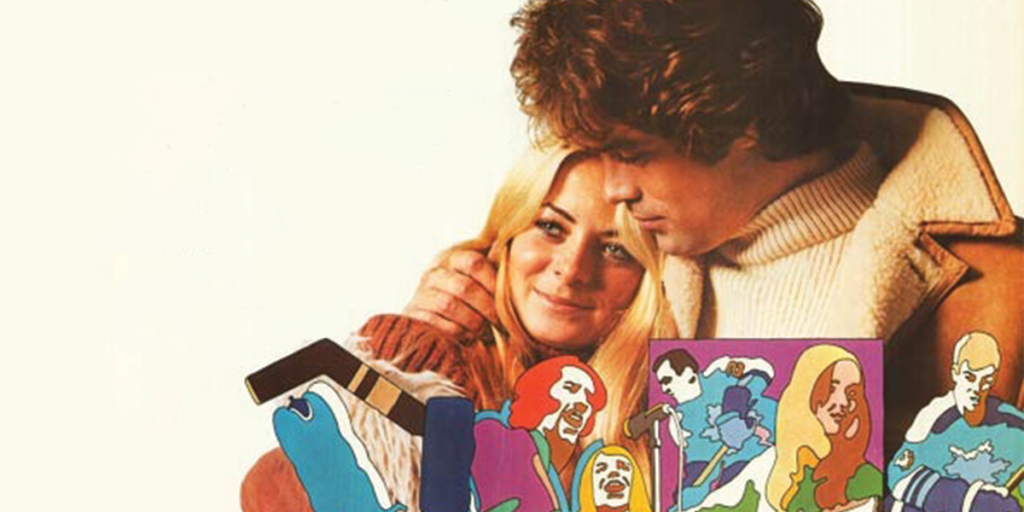

Face-Off is not the Face/Off you’re thinking of (the / is the key difference). This Face-Off is a 1971 Canadian film directed by George McCowan that stars Art Hindle (of Black Christmas and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) fame) as a hotshot young hockey star for Canada’s team the Toronto Maple Leafs (yeah, I said it) who begins dating a flower-power rock n’ roll leading lady played by Trudy Young (of Razzle Dazzle(?) fame). This, ladies and gentleman, is about as Canadian as you can get.

McCowan’s film works great as an example of Canadian content, as the film was partially funded by what is now Telefilm Canada. Visibly present is product placement for Molson Canadian. This is in addition to being a film partially about hockey, that features many scenes that take place in the Ontario countryside, and again, features Canada’s team the Toronto Maple Leafs (who we will have to late discuss in more detail to really grasp what a mess Face-Off is). I imagine that this is what people think of when they cringe at the thought of Canadian content.

At the time of the film’s release, this was also the prevailing sentiment. To pull an extremely amusing quote, Martin Knelman described Face-Off in a review for the Globe and Mail as being “downright head-clutchingly terrible.” The film managed to gross a then record take for a Canadian film, it is estimated that the McCowan’s feature still needed to double its gross to recuperate its investments. John Laycock dubbed the film for The Windsor Star as being “strictly a minor league entry.” Safe to say this was not a grand foray for the Canadian film industry into the larger scale cinematic world.

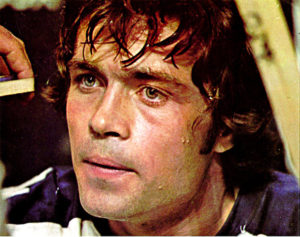

Part of what largely holds back Face-Off is its disjunctive structure. Within the first twelve minutes of this film, we’ve seen short snippets of the most important moments of Billy Duke’s life, from his first time on the ice, to the contract negotiations on his first NHL contract. Quickly relaying important events isn’t the issue, it’s the nature of how they’re relayed. Most films choose to deliver this information in the style of a montage. McCowan instead chooses to use a series of short scenes, maybe totalling two-minutes in length. The effect is jarring. Each of these scenes feels far too short for us to really feel like we’re coming to understand each character, and instead feels purely conducive to an exposition dump.

In a way, this disjunctive structure could be a result of the fact that the film seems to struggle with exactly what it wants to be about. Hockey is one of the most difficult sports to portray on film, due to the nature of ice skating as a prerequisite. To work around this, Face-Off partially partners with the NHL to use footage taken from actual games. This is a positive in that the game footage looks real because it is. This is a negative in that the film’s use of hockey footage never feels organic and natural to the story. To compound this, Art Hindle’s hockey playing counterpart, Jim McKenny, scored exactly 4 goals in the 1970-71 season. The drawback of this is that while we’re constantly being told that Billy Duke is young phenom, we rarely see evidence of it. Most of Duke’s on-ice scenes are scripted, and of fighting. No wonder Sheri Lee Nelson (Trudy Young) thinks the sport is too violent.

Speaking of Sheri Lee Nelson, while Face-Off wants to be a hockey story, it also wants to be a love story. It doesn’t succeed in either respect, but it does try! Nelson is the character most short changed by the film’s indecisiveness about being a hockey film, or a romance. Her character mostly serves to act as a sort of McGuffin about Billy’s hockey playing. Should he choose her, who doesn’t like the hockey, or the hockey? Yet, to add to this, Nelson is a borderline drug addict (the film gets weirdly preachy in one instance about pot being a gateway drug to cigarettes, which feels out of order) who may need Billy to save her. Wait, you mean to tell me it’s time for another hockey sequence that won’t address these issues that have been brought up?

This is the cycle that Face-Off undergoes: fast hockey action, followed by another layer to this tragic romance, followed by the perpetual slandering of Billy Duke for being a selfish show-off. Rinse and repeat, and the last stage of that cycle proves particularly aggravating when you consider the fact that we really know very little about Billy’s hockey playing ability other than, “he’s very good.” Everything seems to move far too fast, from one moment to the next, with little time to breathe, generating a feeling of tonal whiplash.

All of this ends up being compounded into some relatively cringe-worthy production values, which are exacerbated by the Toronto Maple Leafs of it all (I told you they were coming). Several Leafs make cameos throughout the film, most notably George Armstrong who is a major supporting character. They’re relatively wooden actors, which is fair because they’re professional athletes by trade and amateurs in the acting department. Nobody said that Basic McRae and Mike Modano had to be award winning thespians in The Mighty Ducks, but the film isn’t partially built around them like in Face-Off’s case.

But since this is a production that involves the Leafs in the 1970s, megalomaniac owner Harold Ballard makes a cameo as a doctor. Not a chance the film gest made without his involvement in some capacity. Face-Off is a bit of a mess, but it’s another example that everything Harold Ballard touched post-1967 turned out horribly. More than that, it’s an example of the most mediocre and disjointed cinema a nation has to offer. Happy Canada Day!