Watching Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers for the first time in a half-a-dozen years, I was struck by the remarkable contradiction of the film’s aging. In a lot of ways, Korine’s ode to the hard-partying debauchery of spring break at the burgeoning beginnings of the EDM dance craze felt instantly dated. Simultaneously, on re-watch I was struck by how timeless the story felt, as if Korine were hell-bent on remaking Scarface about a generation raised on the glossy music videos of Britney Spears in the early 2000s through after school afternoons spent splayed out in front MTV. In some respects, this is a classic story. In other ways, it can be seen as a truly committed to vision. Ultimately, every generation gets the opulent gangster film it deserves. Scarface, after all, has been remade twice.

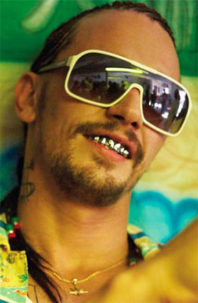

Released somewhat wide just in time for spring break of 2013, Korine’s film tells the story of four college aged girls looking to have the best spring break possible on the Florida beaches, where they meet local drug dealer turned rap artist (or is the other way around) Alien (James Franco) who leads the four young girls into a seedy underground of violence and drugs. Spring Breakers was both the financial coming out party for both the semi-infamous writer/director and studio A24. The film is often attributed as helping grow the indie darling studio, who had released just two features prior to Spring Breakers, but would eventually go on to distribute many of the decade’s most innovative and well-regarded films including Moonlight, Lady Bird, and Hereditary. Thus, Korine’s film links both the director and the studio together, and discussions of either half eventually return to the respective other side.

Let’s tackle Korine and his film first before we get into A24. At the time of its release, Spring Breakers was just the fourth film in the director’s semi-notorious filmography. A household name amongst cinephiles, but a relative unknown amongst the masses, Korine got his start in the mid-nineties through writing the semi-autobiographical script for Larry Clark’s Kids. Despite eventually leaving the project, the considerable controversy and outcry Clark’s film gained Korine and audience with producer Cary Woods, who would go on to produce his debut feature Gummo.

Gummo solidified two major factors of Korine’s signature style. The first being the film’s aggressive subject matter and unflinchingly grotty portrayal of societal margins. The other, which generated far less controversy, was his use of a wildly incoherent plot structure focusing on episodic moments as opposed to linear narrative progression. For Korine, Gummo’s non-actors were essential to creating the look and feel of “a real America,” an America hidden away from the usual one. Some (of the many) criticisms lobbed at him emphasize the director’s self-indulgent nature. In a way, he could be best described as a cross between a filmmaker very cognizant of the intended look and feel of his intended vision, and one so similarly hell-bent on combining said look and feel with obnoxious imagery that the imagery potentially overpowers the audience’s ability to appreciate said vision. An apt metaphor for Korine’s filmmaking sensibilities could very well be painter Jackson Pollock. The ability to enjoy the vision at hand exponentially relates to the ability to reconcile with the fact that the vision looks like that.

Of all of his films, Spring Breakers is likely the most accessible of all of Korine’s “visions.” Thus, if there were ever a film within the director’s “œuvre” that would require the least amount of reconciling with, it would be Spring Breakers. Mostly shot on 35mm, the film mercifully features less format jumping than earlier works. The film is less concerned with a home video aesthetic, and is more concerned with generating a music video like one. Lights become his filter of emphasis, alternating between various shades of neon. In an early scene, protagonists Brit (Ashley Benson) and Candy (Vanessa Hudgens) find themselves sitting in a completely darkened lecture hall save for the alternating neon lights of computer screens. In many of these moments the light reflects of the skin of its characters, changing their various complexions as if Korine were spray painting the very skin of his characters.

Transformations play a heavy role within Spring Breakers. The millage of the road to Florida and other warm weather locales, seems to act as an opportunity for younger people to let loose within the spring break mentality. Throughout the film, youth is frequently alluded to. On multiple occasions, clips of the TV show My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic can be seen in the background. Two of the main four actresses, Hudgens and Selena Gomez, are well known for their various roles in Disney ventures aimed at early teenagedom like High School Musical. In promoting the film on her Facebook page, Gomez specifically cautioned her younger fans with a warning that the film was, “not for [her] littles.” Her comments could very well be read as a metaphor for the film she was staring in, a film about littles trying to be not so little anymore.

The most obvious “not so little anymore,” transformation within Spring Breakers probably constitutes the young bodies of the film. The opening two and a half minutes of this film are eye-opening, and filter the remaining ninety plus. Set to the most ridiculous Skrillex song imaginable (the EDM artist scored the entire film), Korine provides us with slow motion music video like footage of innumerable young partiers, all scantily clad, most topless, all either bouncing up and down or suggestively eating popsicles. The camera doesn’t so much gaze, as it leers. One particular slow zoom pushes from a medium close up of one young woman’s face and bare chest, into a close of up the latter. The effect is fairly obvious. Spring Breakers is a parade of heavily sexualized imagery. It’s no wonder that some such as Heather Long of The Guardian, accused Korine of promoting rape culture.

I would argue that this is a more than fair complaint. In this instance, it’s hard to tell if the provocateur is merely provoking or actually attempting to make a statement. There’s a little too much glee the camera seems to get out of the throbbing mass of nearly naked bodies for Spring Breakers to be an entirely successful satire. But at times the absurdity of the situation occasionally shines through. In one instance, voiceover of Gomez calling her grandmother plays overtop of the initial forays into spring break culture by our young heroines. “We saw some beautiful things,” Gomez intones while the are girls urinating in an alley. The absurdity is deeply ironic. We are very much aware that this debauchery isn’t particularly beautiful, even if the characters aren’t. Are the filmmakers aware though? Maybe, maybe not. This is largely what makes filmmakers like Korine so divisive. So little of the work is done for you in regards to the imagery created.

Spring Breakers isn’t only about sex. Sex is just one of the many points of interest to the characters within Korine’s world that includes violence, wealth, and ultimately power as the pillars upholding its existence. At the very end of the film’s aforementioned opening sequence, the firing of a gunshot goes off. One particularly memorable sequence involves Alien being forced onto his knees by Brit and Candy who are holding guns. When Brit and Candy force the guns into his mouth, Alien essentially performs fellatio upon the weapons turned phallic symbols. Sex and violence become intertwined in this moment, and within equating those two comes power.Spring Breakers is also a film obsessed with the now. The elliptical editing style seems to discombobulate time and space, obfuscating temporal boundaries and turning the film into a series of momentary snapshot. The film never seems to flashback, instead preferring to flashforward, as if the film were so obsessed with getting to the next moment that it cannot even stay in the current one.

All of this contributes to a very unique and arguably singular vision. While you’re never entirely certain of Korine’s intentions, it’s similarly impossible to not acknowledge that something is intended. To bring the studio A24 back into the equation, if Spring Breakers really is the launching pad for the studio, then the reputation of A24 is largely tied to the aspirational production mythos of films like Spring Breakers. The auteur is an old-fashioned concept in cinema studies. It largely came about as a result of Cahiers du cinema journalists who felt that an emphasis on the vision of an artist would legitimate the form. In some capacities it’s a concept that is a bit ridiculous. Even for films with very pointed visions such as Korine’s, the director isn’t the sole creative entity. There’s a number of different actors on screen, Douglas Crise is credited as the editor, Gaspar Noe’s usual cinematographer Benoît Debie is responsible for the camera work, and there’s at least a dozen different producers with a stake in the film. All of these individuals largely contribute to the eventual end product, and it’s unlikely the film exists without them.

At the same time, there’s something comforting about the auteur theory in a modern-day sense. In a world where the movies seem to exponentially grow each year, it is somewhat comforting to feel as if there are smaller and more personal projects that exist. The stratification between the big films and the small ones continues to widen as franchise filmmaking progressively increases its stranglehold on the mainstream box office. Maybe this is why some hold on so dearly to A24 as a concept; the studio for filmmakers, instead of the one for properties. Messy films are usually attached to the former and not the latter. Therefore, maybe this alludes to the fascination we have with messes, especially with messy films made in a modern-day context. To mitigate risk, films become pre-packaged in a sense. In contrast, messy films have very little pre-packaging. Some assembly is required, usually more than you’d probably like. For films like Spring Breakers, you have to be prepared to assemble pretty much all of it.

At the same time, there’s something comforting about the auteur theory in a modern-day sense. In a world where the movies seem to exponentially grow each year, it is somewhat comforting to feel as if there are smaller and more personal projects that exist. The stratification between the big films and the small ones continues to widen as franchise filmmaking progressively increases its stranglehold on the mainstream box office. Maybe this is why some hold on so dearly to A24 as a concept; the studio for filmmakers, instead of the one for properties. Messy films are usually attached to the former and not the latter. Therefore, maybe this alludes to the fascination we have with messes, especially with messy films made in a modern-day context. To mitigate risk, films become pre-packaged in a sense. In contrast, messy films have very little pre-packaging. Some assembly is required, usually more than you’d probably like. For films like Spring Breakers, you have to be prepared to assemble pretty much all of it.