The characters in Wong Kar Wai’s films lives forever in generations of cinema lovers. And that’s because of how they represent a vision of love. Perhaps there needs to be a critical reassessment of those characters. A world full of love struck characters has holes in it in the eyes of cynics. But that feels like an impossible venture. Personally speaking, my exposure of him started through fashion forums where images of his films will inspire an unconscious bias towards him. Images, after all, can win over plot in a visual medium. But before the cynics come flooding in, there’s a touring virtual retrospective of his films making a stopover at TIFF. It is bound to make new viewers fall in love with these characters the way previous generations did.

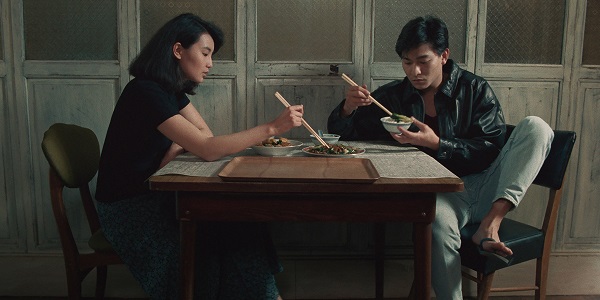

Let’s start with the way I started into Wong’s filmography, with In The Mood For Love, which presents Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung’s elegance. That characteristic shines through in still images as much as they do in film. Looking back, the film’s premise brings out the heterosexual white woman in me. In their situation, the last thing I would want to do is to have dinner with the other marriage’s offended party. But that’s exactly what Chow Mo-wan (Leung) and Su Li-zhen (Cheung) do. They also go further, renting hotel rooms where they reenact their spouses’ transgressions and even staying in each other’s apartments. Cheung’s restraint and warmth here makes some critics argue that she should have been the first Asian woman to earn a Best Actress Oscar. I disagree, but the Academy did rob her at least of a nomination.

Anyway, these hangouts are almost impossible to do in Mo-wan and Li-Zhen’s building where everyone knows everyone’s business. And in 1962-era Hong Kong at that, where proximity means both community and gossip. Wong, as he shows here, suspends disbelief while proving that love can bend that line. That love upends what characters tolerate and makes them behave irrationally. That behavior takes place in a world that seems, visually, like a jade shining through darkness. When we think colorful we think light, but there’s enough darkness in his aesthetic to remind his viewers of the burden of his characters’ inescapable melancholy.

Wong wasn’t so melancholic in his earlier films. As Tears Go By is the auteur’s early and possibly only misstep, but it belongs in the retrospective just because it shows the seeds of his ideas. The soundtrack, despite using contemporaneous songs, feels nostalgic. It depicts two lovers’ (Cheung and Andy Lau) permutations through the criminal underworld in Hong Kong. This is also one of three of the retrospective’s deep cuts and this one, as messy at it is, is a mess taking place in turquoise and brownstone.

Hong Kong isn’t the only place that inspires Wong. In Happy Together he takes his viewers to Argentina, where two gay men from Hong Kong live. The film has a reputation of being a melancholic and tragic gay love story, but it feels more like a story about two gay men who shouldn’t be together. Or maybe they should be together to save some poor, helpless third party of their toxic energy. Lai (Leung) takes odd jobs to support Ho (Leslie Cheung), but there’s a possibility of escape as Lai befriends Chang (Chang Chen).

Happy Together belongs in the section in Wong’s filmography where dialogue is exclamatory. But his loving close-ups of his three leads shows the coexistence of beauty and chaos. Those two co-exist for a while, anyway, and all three must eventually choose one of the other. There are also visual contrasts here. Black and and white turns to color, and the green interiors are a refuge to the sun baked Buenos Aires streets. Buenos Aires seems like an appropriate place for a love triangle. It’s a surprisingly cosmopolitan city where characters flock to, scared of how uniform their homes are becoming.

But there’s no place like home, a place that he depicts in trilogies and diptychs. One half of such a diptych is Chungking Express, a film I can’t write too much about because the boss wants to, but all I’ll say is that it involves a lot. That lot includes a food service worker (Faye Wong) breaking into a cop’s (Leung) apartment. Both also get career changes which, you know, happen.

Wong planned two more stories for Chungking Express but those two ended up having more flesh in their own film in Fallen Angels. Its first story involves killers (Leon Lai and Michelle Reis) and the woman (Karen Mok) coming in between them. And the second involves a non-speaking ‘pop up businessmen’ (Takeshi Kaneshiro) and a woman who has to deal with her romantic competitors (Charlie Yeung). This is one of his louder film, which strangely enough makes borough boys like me miss the chaos of downtown at 3AM.

Fallen makes viewers wonder where all the downtown kooks are and if they can find love or if they’re stuck like we normal people are. And in depicting people who are possibly neuro-atypical, Wong and his regular DP Christopher Doyle have their most naturalistic aesthetic. It lets the characters transform and transport the place they inhabit. To the world, the 90s was the end of history. But the characters here were holding on to something instead of embracing an understandable scary new beginning in their lives.

The freedom in most of Wong’s movies feel diametrically opposed to the fatalism in The Hand, about a tailor (Chen) and a sex worker (Gong Li). Both have moments where they move like sketches in a graphic novel, and there’s an attention to detail here. After all this is a movie, a short one, tangentially about fashion. This is Ophuls and Dumas in 1960s Hong Kong, where lovers handle each other when they’re at their worst.

Dramas show people at their worst moments but Days of Being Wild has better moments. Sometimes, characters either find refuge in love, and at others, they make decisions going from bad to worse. This is Wong’s early attempt at depicting a four-way relationship in, again, 1960s Hong Kong. The first story involves a petty criminal, York, (Leslie Cheung) and a reforming showgirl, Leung Fung-ying (Carina Lau). The second involves a concessions worker, Su Li-Zhen (Maggie Cheung) and a cop, Tide (Lau). All four find, lose, and run into each other.

Days is Wong and Doyle’s visually darkest movie but they somehow make gray look less metallic and more jewel-like. There are minimal period touches here, making love and youth seem universal. There’s also the reveal that York is the son of a Filipino aristocrat which gives Wong an excuse to capture the Philippines and its few Chinatowns. Viewers can think their way out of love, or out of how others love each other, but Wong always know how to pull us back in.

Rent the films in The World of Wong Kar Wai at digital TIFF Bell Lightbox. The retrospective starts at December 4. Find out how to rent the movies at digital.tiff.net.