If we’ve learned anything from the complete systematic and moral failure of our patriarchal capitalist society, it’s that men are generally selfish, whiny, petulant and incredibly arrogant babies. Toxic masculinity is, sadly, here to stay; none of us are above it and no one should be spared critique. Therefore, it’s nice to see modern cinema continue to grapple with the controlling tendencies of the male species, particularly in the realm of otherwise routine genre tales.

Kourosh Ahari’s The Night has a classic horror-movie set-up – a family gets lost on a dark drive and must take refuge at a sinister hotel – but places it within a timely context. The family in question, the Naderis, are Iranian immigrants, with the wife, Neda (Niousha Noor) coming over to the US more recently to join her husband, Babak (Shahab Hosseini). With a newborn child between them, however, the cracks have already started to form, outlined in the film’s opening sequence as they fractiously attend their Iranian friends’ house for dinner. But where they are at least initially afforded the warmth of a friendly home, once they leave for the night, any sense of external comfort completely melts away.

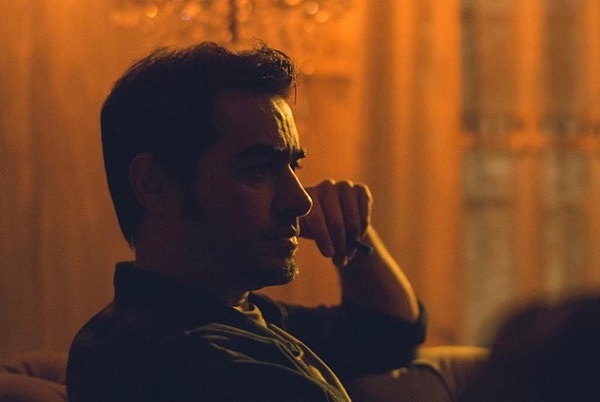

The bickering starts almost immediately and the main culprit is, unsurprisingly, Babak. Exhaustingly grumpy and a little drunk, he nevertheless insists on driving home, even though their dinner guests welcomed them to stay over. So when he promptly gets lost on the endlessly similar streets of Los Angeles, Neda lets him hear it. Then, in one of those foreboding horror movie coincidences, they just happen to come across an ornate old hotel, a beacon in this strange and scary foreign environment. Neda senses something is off. But with a child to think about and no idea where they are, there isn’t much of a choice but to go in and get a room.

Ahari expertly flips the tourist-in-a-scary-foreign-land trope of so many xenophobic American films on its head, highlighting how America is the scariest place of all for a large population of immigrants. But Babak really becomes the central problem here, due to the fact that he’s just a complete asshole. Clearly resentful of Neda for no other reason than that she cuts into the personal freedom he enjoyed (among other things…) while she was still back in Iran, his typical response is to withdraw and act like as much of a child as their baby.

Stomping into the hotel lobby, Babak is also ready to take his anger out on anyone else, affecting an air of pointed condescension towards the elderly concierge. Upon getting their room keys and heading to the elevators, Babak notices an unnerving painting on the wall that shows a man looking in the mirror at a reflection that has turned its back, a giddy sign that a much-needed comeuppance will be in store.

Clearly inspired by canonical classics like The Shining (although anyone who’s watched Netflix’s recent Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel will no doubt feel some parallels), Ahari has an iron grip on the spooky stuff that follows, creating a pervasive sense of dread that engulfs the couple. The hotel steadily warps the their senses, causing them to go chasing after a young boy through the winding hallways or think that they’re having interactions with each other when they’re not even in the same place. In one of the film’s scariest scenes, the arrival of a police officer at their hotel room door sets the stage for a clever ghostly prank. At which point, it becomes painfully apparent that the sun won’t be rising until the secrets that this couple harbour from each other are out in the open.

In ultimately dealing with these secrets, The Night does stumble a bit in the final act, sidelining Neda’s perspective somewhat in favour of Babak’s spiral into madness, resulting in an unnecessary climactic detour that only serves to muddle the proceeding events. But Ahari eventually manages to reign it in, summarizing his film’s thesis with a gut-punch of a final scene that turns Babak’s refusal to own his faults into a one-way ticket to Hell itself.

*******

There isn’t any need for the supernatural in Shatara Michelle Ford’s Test Pattern. The real horrors in her hot-button debut feature are all too concrete, becoming the catalyst for an incredibly assured look at the slippery ground Black women stand on every day in the US.

Yet things start off on a surprisingly sweet note in this Austin, Texas-set psychodrama, as we’re introduced to the burgeoning interracial relationship of career woman Renesha (Brittany S. Hall) and laid-back tattoo artist Evan (Will Brill). After awkwardly asking for her number at a bar, Evan shyly woos Renesha, creating a bond that seems unshakeable. Flash-forward a bit and the couple is now living together, with Renesha excitedly starting a new job fundraising for a non-profit animal organization and Evan finding success with his home-based tattoo business. Things are perfect… until they aren’t.

With a fulfilling first day on the job under her belt, Renesha meets her friend Amber (Gail Bean) for drinks, where two frat-dude types promptly begin to hit on them. With Amber receptive to the attention, Renesha is put in an awkward position, not wanting to leave her friend alone but desperately trying to avoid one of the guy’s overt flirtations. In short order, she has a few drinks, starts to feel woozy and, as is frighteningly common in our never-ending rape culture, eventually wakes up in an unknown bed. Her immediate distress is met with the typical peevish confusion and claims that “she wanted it” from her aggressor, who takes her back to her neighborhood before driving off to never be seen again.

But for Renesha, the nightmare is just beginning. Almost immediately, Evan pushes her to get a rape kit, even though she really just wants to rest. Nevertheless, he insists, driving his weary girlfriend to the nearest hospital. But after waiting forever, they are told that while the hospital does indeed have rape kits, no one on staff is qualified to administer them. Meaning, they’ll have to try somewhere else. So begins a Kafkaesque ordeal of Evan frantically driving Renesha from hospital to hospital in a vain attempt to try and get the ball rolling on bringing her assailant to justice.

Beyond dramatizing the disgusting inaccessibility of basic medical care for a rape victim, the disturbing aspect of Test Pattern becomes Will’s change of character throughout. Initially warm and lovable, Will becomes a man obsessed with the quest for the rape kit, to the increasing detriment of Renesha’s mental health. Getting angrier and more incredulous with every rejection, he affects a faux-outrage about the condition that they find themselves in, even though Renesha is already well-aware of the bureaucratic and legal headaches that lie in wait for her.

And yet Will continues to make her traumatic experience completely about himself, especially as a white man used to getting his way, ultimately becoming a perversely racist issue of ownership. Will isn’t really mad for Renesha. He’s mad that another (also white) man has trespassed on what he perceives as his property, a sentiment that begins to retroactively taint their past happy courtship, particularly as you begin to see that his quest to catch Renesha as an object was always present just under the surface. Will ultimately becomes almost as indistinguishable to Renesha as her rapist.

With strong, naturalistic performances from both Hall and Brill in the central roles, Ford hits us with a serious double whammy, starkly displaying the gender- and racial-based violence that Black women have to tolerate while the dramatic ignorance of white men continues to dominate. Keeping the breakneck pace of a ticking-time-bomb thriller, Ford refuses to come to any easy conclusions by the end, leaving the state of Renesha and Evan’s relationship up in the air. Because for all the good intentions that Evan thinks he may have had, he is, much like Babak in The Night and men in general, unable to look himself in the mirror and see that he’s the biggest part of the problem.

- Release Date: 2/19/2021